Above the waves

Exploring and baselining the marine habitats around Tayvallich estate

By David Smyth, Marine Rewilding Lead at Highlands Rewilding

When most people think of Highlands Rewilding and the Tayvallich estate they tend to focus on the unique terrestrial flora and fauna that flourish within the sites of special scientific interest. However, the coastal environment that surrounds the estate from the high shore to the low shore is home to some equally impressive marine habitats.

The estate sits within the boundaries of the Loch Sween Marine Protected Area (MPA), which incorporates the main basin of the loch and its many arm-like extensions. The MPA was designated on the presence of four specific priority features: burrowed mud, native oysters, maerl beds, and subtidal mud with mixed sediment communities. In addition to these rare ecosystem service-rich habitats, the estate is home to the equally important intertidal habitats of saltmarsh, seagrass meadows and native oyster beds.

These intertidal zones fall within the boundaries of the estate and the marine team is presently mapping and assessing their conservational health. Highlands Rewilding consider themselves custodians of these marine habitats and, as such, have an obligation to monitor, maintain and, where necessary, repair their condition to a pristine functional level.

Surveying intertidal zones – how it works

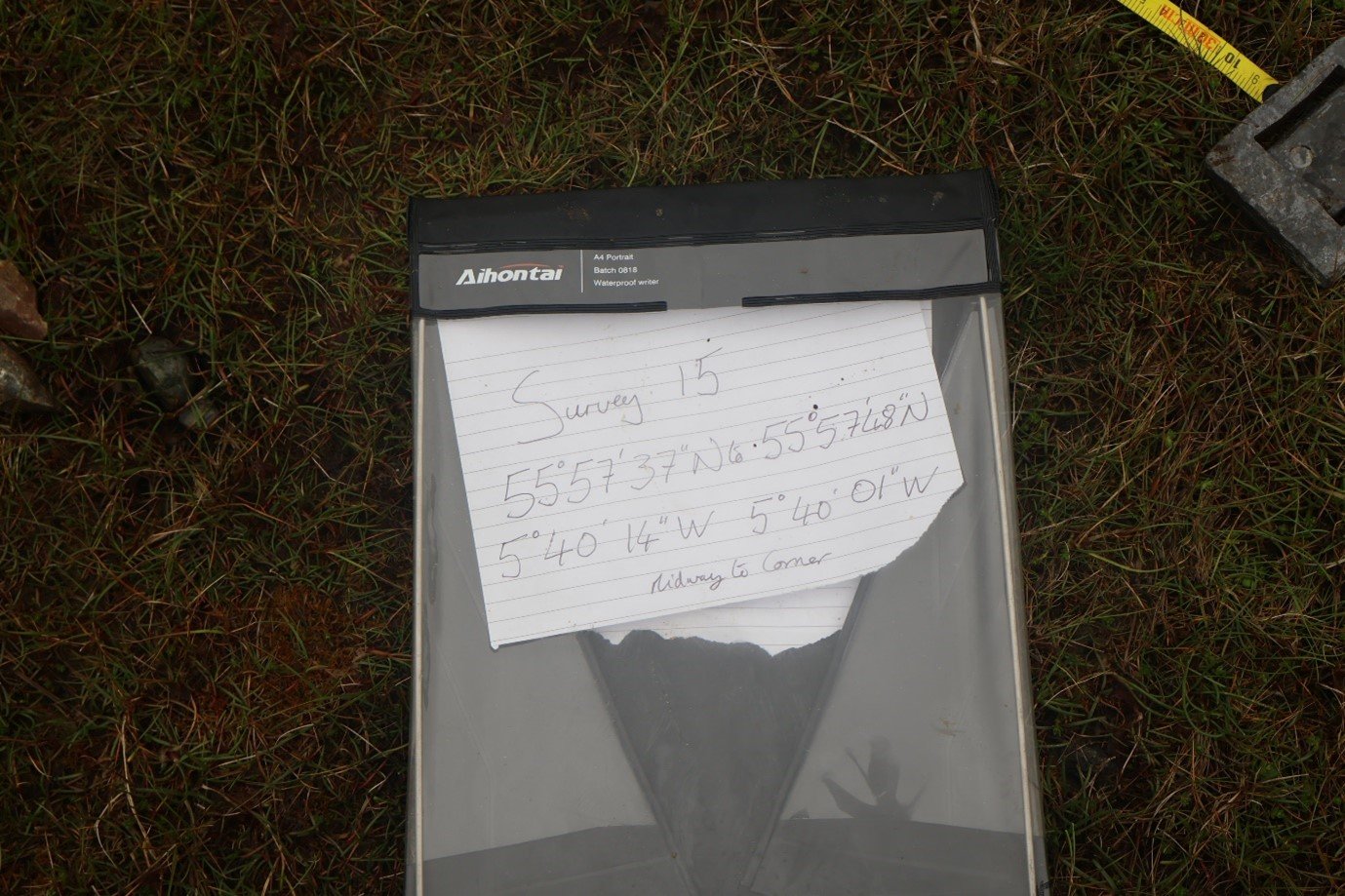

In order to get an accurate assessment of the intertidal, it requires boots on the ground scientific methodology using basic tried and tested sampling. A typical survey will involve a reconnaissance walk along the selected survey site on the first low tide. During the recon, GPS coordinates will be taken at the start and finish of the identified habitat type. Then, on the second low tide, a transect and quadrat survey is carried out. A 30m measuring tape is laid from the high to low shore. The surveyor walks the length of the tape, deploying a grided quadrat 25 times, taking photographs of the contents within each quadrat. These images in combination with the coordinates and survey length act as a baseline guide for what is present at that point in time. This photographic record allows for the monitoring of the site through a simple comparison of the digital stills. The same methodology is used when mapping and monitoring subtidal marine habitats and ensures a scientific rigor throughout our work which is recognised by public bodies, private consultancies and university researchers.

Biotope: the region of a habitat associated with a particular ecological community.

Once all the images have been analysed, a code denoting the habitat type can be assigned to the section of the surveyed intertidal zone.

If we say, hypothetically, that the last section of the transect from 20 to 30 meters consists of seagrass on a muddy sandy substrate, we can look up the Joint Nature Conservation Committee government recognised biotope code for this habitat which is, LS.LMp.LSgr.

This code is read as:

LS. Littoral sediment, which just refers to a sediment and not rock on the mid-shore.

LMp. Littoral macrophyte, which means a plant found on the mid-shore.

LSgr. Littoral seagrass bed, a seagrass bed found on the mid-shore.

Fig 4. Mid-shore (Zostera noltii) seagrass bed

Each code is accompanied by a list of species associated with the habitat type; these are indicators of health and have been identified and assessed by taxonomists specialising in that environment.

Therefore, if we return in a year to survey our hypothetical mid-shore seagrass bed and the survey data does not allow us to assign a seagrass code because we are missing seagrass coverage or several key species, it is a clear indicator of environmental change.

A map of the intertidal biotope codes around the Tayvallich estate will prove a powerful tool in the long-term management of the habitats found in this highly sensitive section of the coastal marine environment.

Indicators of climate change – spotlight on saltmarsh, seagrass and native oyster beds

With the ever-intensifying effects of increased rainfall and rising sea temperatures, vulnerable habitats like saltmarsh, seagrass, and oyster beds will be some of the first to indicate change.

Saltmarsh

These three intertidal habitats (Figures 5, 6 and 7) follow a connectivity from land to sea. Saltmarsh provides protection to shorelines from erosion and flooding by buffering waves and trapping sediments. They reduce flooding by absorbing rainwater and protect water quality by filtering terrestrial runoff. They are highly biodiverse, supporting migratory birds, specialist plants, indigenous insects, juvenile fish and crustaceans. They act as natural carbon sequestration sinks, storing carbon both in the plants and sediment. A hectare of salt marsh can capture two tonnes of carbon every year and store it for millennia if undisturbed.

If our Tayvallich saltmarsh starts to show evidence of species loss or erosion it can suggest increased freshwater run-off. However, all is not lost as we can counter this through restoration. A simple procedure which is currently underway in many parts of flood vulnerable parts of the UK.

Seagrass meadow

Our next early warning habitat is the seagrass meadow, which supports a high level of biodiversity, and provides essential nursery grounds for commercially important fish and crustacean species. They also act as coastal protection buffers by absorbing wave and storm impacts. Seagrass environments are efficient carbon sinks and can store carbon 35 times faster than rainforest and despite covering only 0.1% of the ocean floor, they store up to 18% of global marine carbon. In the case of seagrass, if we encounter die back during the summer months in combination with high levels of silt in the water. It indicates increased sediment levels entering the water column, which in-turn cuts the availability of light to the seagrass, decreasing growth. If the sediment load is heavy, it can settle out on seagrass and smother it completely. Again, if this becomes an issue in the future, we have the expertise within the marine team to address seagrass degradation through restoration.

Native oyster

Our third indicator is native oyster Ostrea edulis, a particularly rare habitat throughout its natural range, with only an estimated 5% remaining from what was recorded in the 1700s. The native oyster is considered an ecosystem engineer with a set of extraordinary services, one oyster can filter over 200 litres of water a day, removing excess nutrients and harmful particulate matter from the sea column, including microplastics. Oyster assemblages form biodiversity hotspots; a single oyster can have over 100 individual species attached to or living on its shell. An established oyster bed acts as a nursery and food station for many fish and crustacean species; it will also stabilise sediments, removing the impact of highly dynamic wave action. The loss of species associated with the oyster, evidence of silt covering their shells or increased deaths within the site’s population are indicators of change. However, once again, Highlands Rewilding can repair any damage through restoration, which is currently underway at over 30 sites in the UK and Ireland alone.

There are many more intertidal habitats within the Tayvallich estate which are indicators of change, and this is why our current work of mapping and coding them is so vital. Highlands Rewilding not only have the capacity to monitor for change but to implement measures which will address the possible environmental issues arising.

In our next marine blog, we will reveal some of the fantastically beautiful habitats beneath the waves that our intertidal early warning monitoring will be used to protect.

To learn more about Tayvallich’s marine surveying, including ‘below the waves’ dive surveys, enjoy our two-part dive surveys video